In 1964, the founding Prime Minister of Singapore, Lee Kuan Yew, undertook a 35-day journey across 17 African countries, including Nigeria. He returned with a clear vision of how to not run a newly independent country. This vision would shape the rise of Singapore.

From Singapore to Africa

Yew had visited to seek support and sympathy for the newly formed Federation of Malaysia, which Singapore was a part of at the time, amid the geopolitical tensions of the Cold War and regional opposition to the federation, particularly from Indonesia’s President Sukarno. The trip allowed Yew to meet and engage the leaders of the newly independent African nations.

This period was marked by many African nations rejecting capitalism and ideas of free trade. They associated it (among other things) with colonialism and adopted its opposite, socialism wholesale. Socialism involved nationalizing industries, government control of prices, imports and foreign exchange and often autocratic governments. In the case of Tanzania and Ethiopia, it meant forcing people out of their homes onto villages. For Lee, the path of socialism being hallowed everywhere in Africa led to certain but ‘unnecessary poverty.’

In his words, “I was not optimistic about Africa.”

Tanzania

In a 2001 interview with PBS, Yew recalled his experience in Tanzania during his visit, and his interactions with Julius Nyerere, its first president. In his words: “Oh, yes, Julius Nyerere is a good Christian. He wanted to do good to his people. He’s a great Christian; he can quote you chunks of the Bible. He was a preacher also. He was a devout Catholic. But he didn’t understand the economics of growth, or just simple economics.

“He thought if you gather people together — I think it’s called “ujamaa,” or some form of communalized agriculture. So he had them all in villages, and they would work their farms. And then they were living together, and the children would go to school, and you can provide health services and so on. It’s the noble objectives. But walking back and forth to your farm, there’s nobody to look after them and so on, and then you have cooperatives that buy the products at uncompetitive prices, so whole thing malfunctions. It was a terrible waste.”

In 1967, Tanzania’s ruling party’s Arusha Declaration nationalized banks, insurance companies and foreign trading companies. From 1973, about 13 million peasants were loaded into trucks, often forcibly and moved to about 8,000 co-operative villages to join in the communal production and marketing of food crops. Many lost their lives in the process. To prevent their return to their homes, their abandoned homes were destroyed by bulldozers. All crops produced by the villages were to be bought and distributed by the government. It was illegal for the peasants to sell their own produce.

Nyerere would leave Tanzania one of the world’s poorest countries. As of 2024, about 49% or 26 million Tanzanians live below the poverty line.

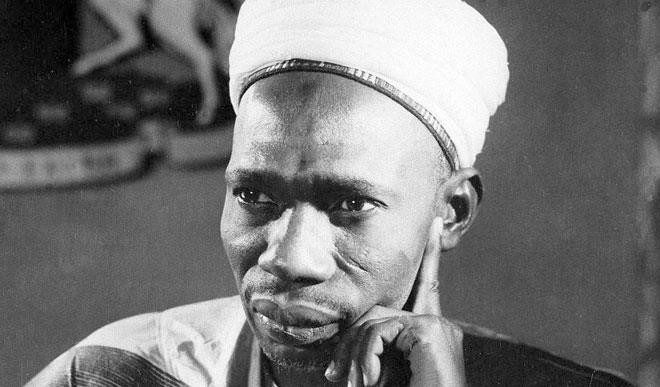

Nigeria

At the time of his visit to Nigeria, Alhaji Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa was Prime Minister. He impressed Lee at the time. The spectacular guard of honour welcome ceremony that was given him upon his arrival coloured his impression of Balewa. It was all done in the manner of the British. There was also the infrastructure of Lagos at the time, which looked very much like that of the British. (Balewa was a renowned Anglophile.) Tribalism, not socialism was Nigeria’s peculiar problem. He noted that Nigeria’s political power was given by the British to the northern Nigerian Muslims, leaving the Christian south feeling excluded and marginalised.

This would unravel two years later, in January 1966, when he returned to Lagos for the first Commonwealth meeting. According to him, Lagos looked like it was “under siege” with police checkpoints lining the road to the Federal Palace Hotel, where Balewa had hosted a banquet for his guests. He saw barbed wires and troops surrounding the hotel and noticed that none of the leaders present left the Hotel throughout the two-day conference.

Reflecting on his visit, Lee would recall in his memoirs: “I thought their tribal loyalties were stronger than their sense of common nationhood. This was especially so in Nigeria, where there was a deep cleavage between the Muslim Hausa northerners and the Christian and pagan southerners.” His haunch about Nigeria was correct. Shortly after the meeting’s conclusion, Balewa was assassinated in a coup led by Nigerian army majors from the Christian south.

The rest as they say is history.

Ghana

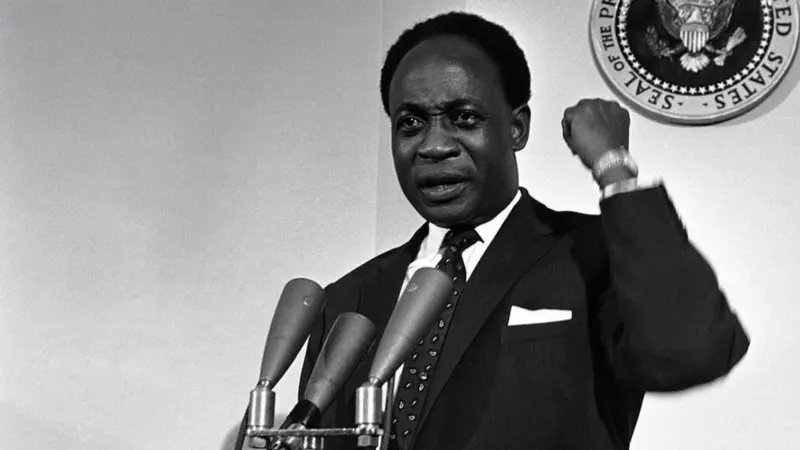

After leaving Nigeria, Yew’s next stop was Accra, Ghana. There, three days later, news reached him that a coup had been carried out in Lagos. In Ghana, he met President Kwame Nkrumah, a charismatic leader who had founded Ghana’s first republic in 1960.

Nkrumah’s vision for Ghana was ambitious. He sought to rapidly industrialize the nation with the aim of reducing its dependence on colonial trade systems. His government embarked on extensive development plans. The most prominent was the construction of the Akosombo Dam, which provided hydroelectric power and was central to his economic strategy. However, these projects were financed through significant borrowing that led to mounting national debt.

By 1964, Nkrumah had introduced a Seven-Year Development Plan that focused on further industrialization. He founded 64 state corporations. However, the implementation faced challenges, including lack of capital and underestimation of the complexities of managing state enterprises. The period saw an explosion in corruption, rising unemployment and a decline in agricultural productivity. At the time of the 1966 coup that removed Nkrumah, only 3 or 4 of his 64 state enterprises were profitable.

Due to his visit, Lee Kuan Yew observed the consequences of Nkrumah’s policies first-hand. He noted that while Nkrumah’s intentions were noble, it lacked pragmatism. Also, corruption and economic mismanagement would inevitable lead to its failure. He left Ghana with his belief in the importance of meritocracy, economic pragmatism and incorruptible governance reinforced.

In his words, “My fears about Ghana were not misplaced. Notwithstanding their rich cocoa plantations, gold mines, and High Volta dam, which could generate enormous amounts of power, Ghana’s economy sank into disrepair and has not recovered the early promise it held out at independence in 1957.”

“I was not optimistic about Africa.”

Lee Kuan Yew’s 1964 African tour gave him of first-hand view of the pitfalls of adopting ideologically charged policies without considering practical economic realities. As Lee saw it, “To rally their people in their quest for freedom, the first-generation anti-colonial nationalist leaders had held out visions of prosperity that they could not realize.”

His experiences and interactions with the new African leaders taught him priceless lessons on the importance of effective governance, economic pragmatism and national unity. These lessons would profoundly impact Lee’s approach to developing Singapore. They taught him the need to emphasize meritocracy, to embrace a market-driven economy and to encourage foreign trade.

The subsequent transformation of Singapore into a global economic powerhouse owes, in part, to these lessons well learned.